First Human Trial of Regenerative Cell Therapy Targets Age-Related and Neural Hearing Loss

UK Researchers Launch Groundbreaking Study Using Regenerative Cells to Repair Auditory Nerve Damage

Hearing loss affects millions worldwide, not just as a health issue but as a disruption to communication, autonomy, and daily living. Traditional options like hearing aids or cochlear implants can help manage the condition, but they don’t address the root cause in most cases. A new clinical trial in the UK is now exploring a different approach by regenerating damaged cells through a novel cell therapy that could change how hearing loss is treated.

Rinri Therapeutics, a biotech company born from years of academic research at the University of Sheffield, has been granted approval to begin the world’s first human trial of a cell therapy designed to restore hearing by repairing the auditory nerve itself. Called Rincell-1, the treatment aims to regenerate nerve cells in the inner ear that are essential for transmitting sound signals to the brain—cells that no current treatment can replace.

A New Approach to Hearing Loss

Most people are familiar with hearing loss that comes from damaged hair cells in the inner ear. But in neural hearing loss—seen in conditions like age-related hearing decline (presbycusis) and auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD)—the issue lies deeper, in the nerve fibers that connect the ear to the brain. Cochlear implants can help, but only if the auditory nerve is still functional.

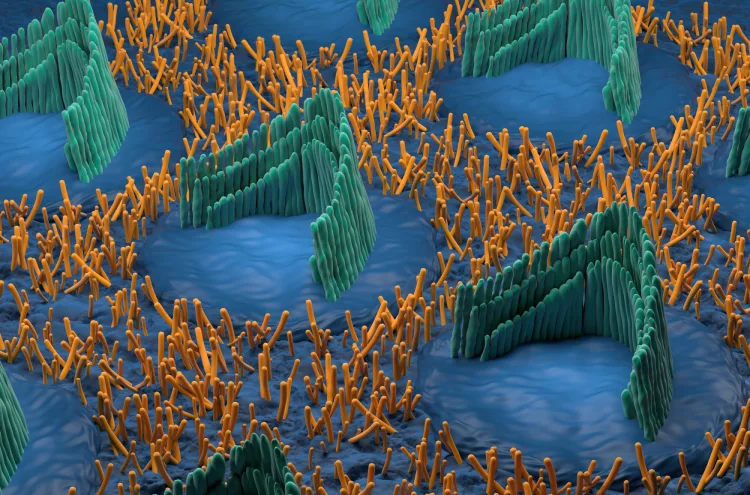

Rincell-1 offers something radically new. It uses lab-grown precursor cells—called otic neural progenitor cells—that are designed to mature into working auditory neurons after being delivered directly into the cochlea during cochlear implant surgery. In essence, it’s like rewiring a frayed cable at its core, not just boosting the signal.

“Instead of just amplifying or rerouting sound, we’re aiming to rebuild the broken connection,” said Professor Marcelo Rivolta, the therapy’s lead scientist and co-founder of Rinri Therapeutics.

Trial Details: Who’s In and What’s Next

The UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has approved a Phase I/IIa trial, which will be conducted at three of the country’s top hearing research centers. The trial will involve 20 adult participants: ten diagnosed with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD) and ten with advanced age-related hearing loss. In each group, half will receive both a cochlear implant and the experimental treatment, Rincell-1, while the rest will be fitted with the implant only.

This isn’t just about seeing whether the treatment works—it’s first about safety. But researchers will also be looking for early signs that the therapy helps regenerate nerve activity. They’ll use real-time data from a monitoring system built into the cochlear implants, as well as speech perception tests and patient feedback.

Within a year of starting, the team expects to gather proof-of-concept data—an early indicator of whether this therapy could become a viable treatment.

Opening a Door Previously Sealed Shut

The auditory nerve endings are buried deep within the skull, protected by bone and difficult to reach. Traditional surgery would require extensive drilling—something too risky and painful for a routine procedure.

Now, thanks to collaborative research across universities in the UK, Canada, and Sweden, a less invasive method has been developed. Described in Nature Scientific Reports, the new approach uses a natural membrane in the inner ear called the round window as a gateway. Through this access point, surgeons can deliver the regenerative cells directly to the site of damage with far less trauma.

“It’s like slipping a message through a mail slot instead of breaking down the front door,” said Professor Doug Hartley, Rinri’s Chief Medical Officer and one of the architects of the new procedure.

Why This Trial Matters

Neural hearing loss impacts more than 100 million people globally, and that number is projected to grow as populations age. Yet treatments have lagged behind, partly because regenerating nerve tissue in the ear was once considered impossible. Rincell-1 is the first attempt to not just manage symptoms but actually change the trajectory of the disease.

The therapy was developed using Rinri’s OSPREY™ platform—a method for producing ready-to-use cell therapies that don’t rely on patient-specific donor cells. That means, if successful, Rincell-1 could one day be available “off-the-shelf,” making it more accessible and affordable than personalized regenerative therapies.

For now, all eyes are on this first trial. It’s the scientific equivalent of planting a seed in long-frozen soil—no guarantees, but a real chance that something once thought lost could grow again.