Deadly Hospital Superbugs Found Feeding on Medical Plastic Are Harder to Treat

New Findings Show How Degraded Medical Plastics Help Pathogens Form Tougher, Harder-to-Treat Colonies

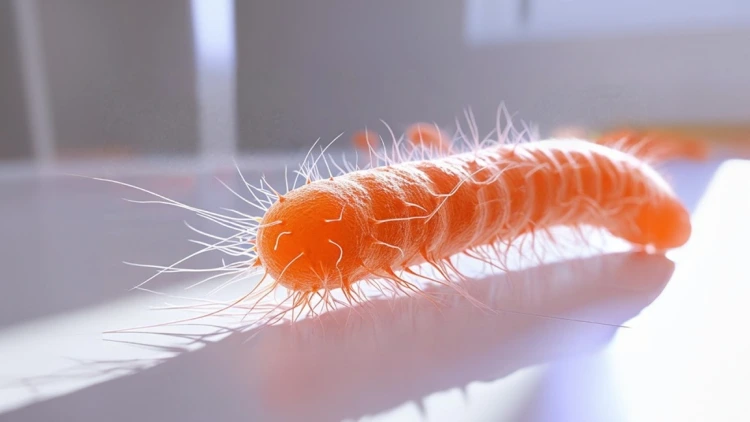

Researchers have discovered that Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common hospital-acquired bacterium, can digest a type of medical plastic used in stitches, implants, and bandages. But it doesn’t stop there. After breaking down the plastic, the bacteria use the fragments to build tougher biofilms — slimy layers that protect them from antibiotics and make infections harder to treat.

This finding, published in Cell Reports, could force hospitals to rethink how they deal with infections and how safe medical materials really are.

A Superbug That Eats Plastic

The bacterium in question, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is already notorious. It’s responsible for serious infections in people with catheters, breathing tubes, or open wounds. What researchers at Brunel University London found is that a specific strain of this bug can digest polycaprolactone (PCL) — a plastic used in medical equipment.

The team isolated an enzyme from the bacteria, named Pap1, and watched it break down nearly 80% of a PCL sample in just seven days. Even more concerning, the bacteria could survive on the plastic as its only food source. Until now, medical plastics were considered safe from microbial attack. That assumption may no longer hold.

Why Biofilms Make This Worse

When bacteria digest plastic, the leftover fragments aren’t just waste — they actually help the bacteria build stronger biofilms. These are sticky layers that bacteria form to protect themselves. As antibiotics can’t penetrate the layer easily, the immune system struggles to clear the infection.

This is one big reason why some hospital infections just won’t go away. The bacteria aren’t floating around in the body — they’re hiding inside protective slime that acts like armor.

Many tools and materials used in modern hospitals are made of plastic — from surgical meshes and drug patches to catheters and sutures. If some bacteria can feed on these plastics and use them to shield themselves, it may explain why certain infections keep coming back even after treatment.

Researchers believe the impact could go beyond just one material. While the study confirmed the breakdown of PCL, signs point to similar enzymes in other bacteria that might affect widely used plastics like polyurethane and polyethylene terephthalate.

What Hospitals Can Do Next

This discovery raises some difficult questions for healthcare providers. Should hospitals start testing medical plastics for microbial resistance? Should we screen pathogens not just for antibiotic resistance, but for plastic-digesting enzymes?

Experts suggest it’s time to rethink infection control. That could mean developing new medical materials that bacteria can’t break down — or at least monitoring bacterial strains more closely in cases of unexplained or recurring infections.

It also means hospitals may need to upgrade their cleaning protocols. If bacteria are lingering on surfaces or devices by feeding on plastic, the usual disinfectants may not be enough.

Plastic is everywhere in modern healthcare. But this study shows that for some microbes, it’s not just packaging — it’s food and protection.

As bacteria evolve new ways to survive in harsh environments, even materials designed to help patients could become part of the problem. Understanding this shift is critical. If we keep assuming plastics are harmless in medical settings, we may be giving superbugs exactly what they need to thrive.

[Source]