World-First Surgery at Alder Hey Saves Toddler from Rare Vein of Galen Malformation

Alder Hey Surgeons Pioneer Open-skull Treatment for Vein of Galen Malformation, Marking a Major Advance in Pediatric Neurosurgery

Three-year-old Conor O’Rourke from Bolton is now “99% cured” of a rare and previously untreatable brain condition, Vein of Galen malformation, after undergoing surgery at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool.

What is Vein of Galen Malformation?

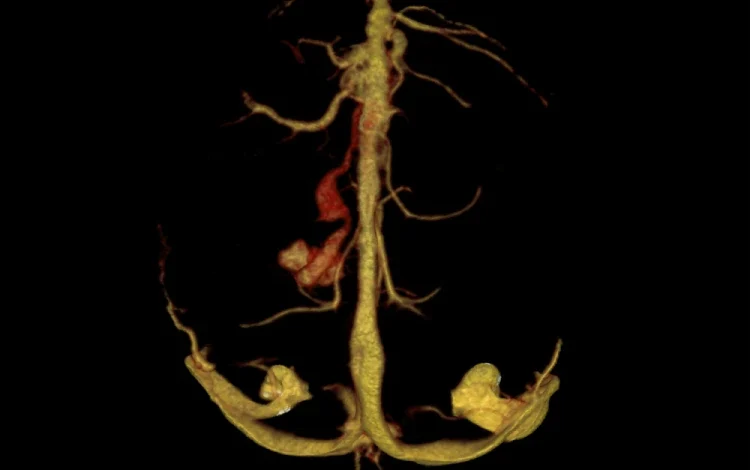

In a person with Vein of Galen malformation (VOGM), arteries connect directly to veins deep in the brain without the normal network of capillaries in between. Without this slowing mechanism, blood rushes at high pressure into the brain’s deep veins, placing strain on the heart and affecting brain function.

The condition can cause a range of serious problems, including heart failure, a build-up of fluid in the brain (hydrocephalus), seizures, developmental delays, and sometimes bleeding within the brain. If left untreated, it carries a very high risk of death—some estimates put mortality at more than three-quarters of cases. Even when treated, the risks remain significant.

Most children diagnosed with VOGM undergo a less invasive treatment known as endovascular embolization. In this procedure, doctors insert a catheter—typically through the groin—and navigate it through the blood vessels until it reaches the abnormal connection in the brain. Special materials are then placed to block the abnormal connections. This technique has transformed survival rates and outcomes for many patients.

A Different Kind of Challenge

For Conor O’Rourke, a three-year-old from Liverpool, standard treatment was not enough. His VOGM was first picked up during a routine check, when a consultant spotted that the shape of his head seemed unusual. Further investigation confirmed the diagnosis—but his case would prove far from straightforward.

But surgeons discovered a major complication—his jugular veins were blocked. This prevented them from reaching the malformation via the normal route, leaving the swelling unchecked and causing damage to his brainstem and spinal cord.

Faced with no viable alternative, neurosurgeon Conor Mallucci and his team at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital designed a new approach. In March, they carried out what is believed to be the world’s first direct open-skull operation for this type of VOGM. By accessing the malformation directly through the skull, they were able to treat it successfully.

Conor’s recovery was described as remarkable. According to his surgical team, he is now “99 per cent cured” and doing well.

Why This Breakthrough Matters

This breakthrough offers hope for children with high-risk cases of Vein of Galen malformation, particularly those whose anatomy or blocked vessels make traditional embolization impossible. By creating an entirely new treatment pathway, it addresses situations where no viable options previously existed and survival chances were low.

Conor’s case also highlights the critical role of early detection—his diagnosis was made possible when an attentive doctor noticed subtle signs during a routine check-up, allowing intervention before further damage occurred.

Finally, it underlines the value of specialist expertise, as Alder Hey is one of only two centers in the UK equipped to carry out such complex pediatric neurosurgery.

Around the world, researchers are also looking at treating VOGM before a baby is born.

In the United States, specialists recently performed the first in-utero embolization, using ultrasound to guide a microcatheter into a fetus’s brain and place small coils to slow blood flow. The baby was delivered with improved heart function and no signs of brain injury. While still experimental, such procedures hint at the possibility of preventing damage before it starts.

The Road Ahead

Even with the best treatment, VOGM is a lifelong condition that requires careful follow-up. Children may need ongoing input from neurosurgeons, cardiologists, neurologists, and developmental specialists to monitor growth and learning.

Historical data from Great Ormond Street Hospital between 2003 and 2008 found that among children who survived treatment, 39% developed normally, 21% had mild developmental delays, and 18% had more significant challenges. These figures show why surgical advances like the one at Alder Hey could make such a difference—not just in saving lives, but in improving how those lives are lived.