Is Being Too Clean Hurting Our Health? The Hygiene Hypothesis Revisited

How Modern Life May be Reshaping Our Immune Systems—And What Science Says About Reconnecting With Microbes

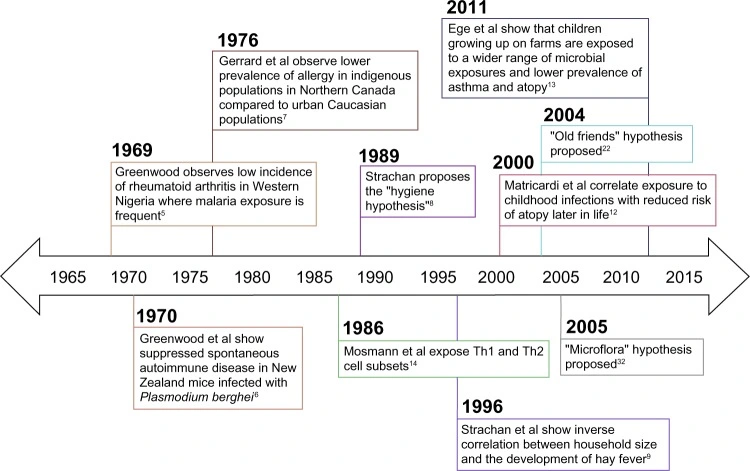

In the late 20th century scientists noticed that allergies and autoimmune diseases were surging in wealthy countries, at the same time that infectious diseases were declining.

For example, Greenwood observed in 1969 that rural Nigerians with frequent malaria had almost no rheumatoid arthritis, and Gerrard in 1976 found far less allergy among isolated Northern Canadian natives than in urban populations.

These observations suggested that some microbial exposures might protect against immune disorders.

In 1989, Strachan published a landmark study revealing that children from larger families were significantly less likely to develop hay fever. He proposed that in households with multiple older siblings, frequent exposure to everyday infections might help the developing immune system learn to respond more appropriately to harmless triggers.

This idea – the “hygiene hypothesis” – posited that modern sanitation and fewer childhood infections might explain rising allergies and asthma.

Evidence from childhood exposure

Since Strachan’s report, many studies have linked more childhood microbial exposure to lower allergy risk.

Common findings include:

- More older siblings: Each extra older brother or sister (and attendant colds/germs) is associated with lower hay fever and asthma risk.

- Attending daycare early: Children in group care get more infections but develop fewer allergies and asthma.

- Household pets: Kids who grow up with dogs or cats have lower rates of asthma and eczema.

- Growing up on farms: A classic study found European farm children (with rich exposure to soil bacteria and livestock) had much less asthma and hay fever than city kids.

- Common childhood infections: Ironically, infections like measles or stomach bug, and even bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, tend to be less common in allergic children.

Together these findings suggest that a broad early exposure to microbes – not just “dirtiness,” but normal infections and environmental organisms – helps the immune system learn to distinguish friend from foe.

How It Works: T-Cells, Balance, and the Gut

Immunologists quickly searched for a mechanism. In 1986, just before Strachan’s paper, researchers described two major T‑helper cell types.

Th2 cells drive allergic reactions, while Th1 cells fight viruses and bacteria. This led to a simple model: early-life infections promote Th1 immunity (via interferon) which suppresses Th2-driven allergies.

The prevailing theory at the time suggested that microbial exposure during childhood encouraged the immune system to develop a healthy balance between its different pathways. Without enough stimulation from infections, the Th1 response would remain underdeveloped, allowing the allergy-related Th2 pathway to dominate.

However, the reality proved more complex. Many other immune players are now known: regulatory T cells (Tregs) that calm immune responses, Th17 cells, and innate signals (like IL-25, IL-33) also influence allergy and autoimmunity.

For example, parasitic worms (helminths) trigger Th2 but at the same time boost immune regulators that dampen allergy. We now think of an elaborate network, where a healthy microbial environment helps develop immune tolerance via both innate and adaptive cells.

The “Old Friends” and “Microflora” Theories

Two major offshoots of the hygiene idea highlight specific microbes:

Old Friends Hypothesis (Helminths)

Graham Rook and colleagues proposed that humans co-evolved with certain harmless microorganisms – especially gut worms and other organisms from the natural environment – that are needed to regulate our immune system.

Experiments in mice show that infecting them with particular helminths or even giving helminth-derived proteins can reduce asthma and inflammatory bowel disease symptoms. This suggests these “old friends” stimulate regulatory pathways (like IL-10 and Tregs) that keep both Th1 and Th2 inflammation in check.

Clinical trials are even testing whether controlled exposure to benign worms might treat autoimmune conditions.

Microflora Hypothesis (Gut Bacteria)

Another modern take focuses on the gut microbiome. The idea is that modern habits (antibiotics, C-section births, sterile diets) disturb the normal bacteria in our intestines, tipping the immune system toward hypersensitivity.

Mice raised in germ-free (sterile) conditions have tiny immune tissues and are much more susceptible to infections and allergies. Likewise, certain gut bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids from fiber and stimulate Tregs, fostering gut health and immune balance.

Several human studies back this gut-microbiome view. For instance, infants who later develop asthma often show reduced gut bacterial diversity in the first months of life.

Antibiotic treatment in the first two years is tied to higher asthma risk at school age (in a dose-dependent way). Babies born by C-section (missing exposure to their mother’s vaginal microbes) have altered gut colonization and weaker early Th1 responses.

In contrast, breastfed infants (with human milk oligosaccharides that feed beneficial gut bacteria) tend to have lower allergy rates.

Not every study is uniform – some cohorts find only weak links – but the weight of evidence suggests modern lifestyles that deplete gut microbes can predispose children to overactive immune reactions.

Health Effects: When Microbes Help or Harm

The hygiene hypothesis specifically arose to explain atopic diseases (allergies, asthma, eczema), which have skyrocketed over recent decades in rich countries.

Under normal hygiene conditions, the immune system learns to tolerate harmless proteins (pollen, foods, dust mites) and prevents asthma or allergies. But without early microbial “training,” the immune system may misfire against these things.

Indeed, children with high microbiome exposure (pets, siblings, farms) show lower rates of peanut allergy, hay fever, and asthma. The same patterns hold for many autoimmune diseases. Type 1 diabetes (where the immune system attacks pancreatic cells) is more common in developed nations than in countries with high infectious disease burdens.

Large studies find each older sibling protects – for example, research showed children with household dogs or many siblings were less likely to develop type 1 diabetes.

Breastfeeding also appears protective for diabetes, and, conversely, kids born by C-section (with altered gut flora) have slightly higher diabetes risk.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis) follow similar trends – Western diet and low microbial diversity are risk factors – and germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice are more prone to gut inflammation, underscoring the role of intestinal microbes. (Research is ongoing to definitively pin down these links.)

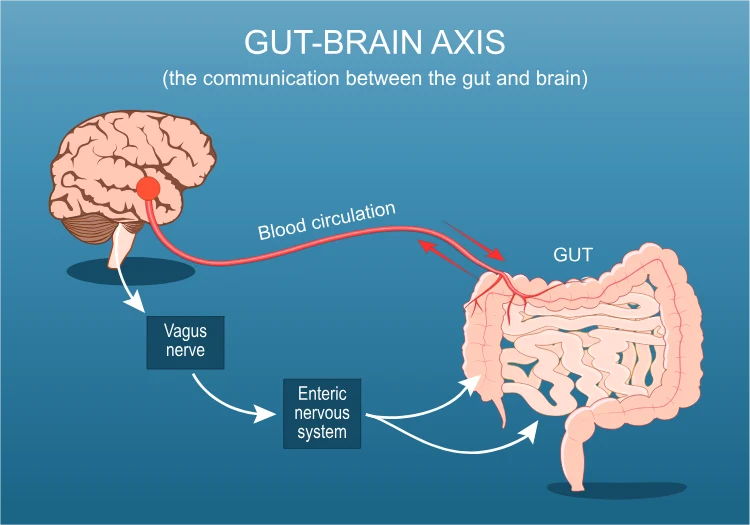

Some scientists have even begun to wonder if “dirt-deprivation” affects the brain. There is a growing body of work on the gut–brain axis: gut microbes interact with the immune system and nervous system through metabolites and inflammation.

It’s too early to draw conclusions, but advocates of the hygiene hypothesis note that proper microbial exposures may support not just a calm immune system but also mental resilience (an idea sometimes called “old friends” and stress resilience). For example, exposure to nature and pets in early life has been linked in some studies to lower rates of later anxiety or autism, though critics urge caution with these interpretations.

On the other hand, we must remember that many microbial exposures are undeniably harmful. Vaccines and antibiotics have saved millions of lives. Robust hygiene practices in hospitals and food preparation prevent deadly infections.

The goal is balance. A modern take on the hygiene idea is “targeted hygiene”: kill or avoid dangerous pathogens (cholera, tuberculosis, novel viruses) while not sterilizing ourselves of all microbes.

For instance, handwashing after the bathroom or before cooking is crucial, but it’s fine – even good – for family members to share some normal germs during play.

Criticisms and Alternative Views

The hygiene hypothesis has its skeptics. Some argue the term itself is misleading – the evidence doesn’t point to household cleanliness per se, but to broader lifestyle changes. A consensus statement in 2016 flatly noted “the term ‘hygiene hypothesis’ is a misleading misnomer.

There is no good evidence that hygiene, as the public understands, is responsible for these changes”.

In other words, it’s not about letting kids eat dirt; it’s about contact with harmless microbes. Critics also say the theory is oversimplified: many factors (diet, pollution, vitamin D, microbiome changes from food) influence immune development beyond just “dirt or no dirt.”

Some specific criticisms include:

Vaccines vs. allergies: By the logic of hygiene, reducing childhood infections (by vaccinating) might increase allergies. Early studies worried about this, but large birth-cohort research has found no evidence that standard immunizations raise asthma or eczema risk. In fact, after controlling for doctor-visit frequency the apparent link vanished. Thus, vaccines do not appear to fuel the allergy epidemic.

Confounding factors: Families with many siblings or farm exposures differ in many ways (diet, pets, rural lifestyle). It’s possible these correlated factors (not pure “germs”) explain the benefits. Some critics note that family size studies could reflect childhood infections or socioeconomic differences.

Similarly, pet exposures might just mean more outdoor time. Ongoing studies (including ones that measure specific microbial markers) aim to untangle these effects.

Alternative or refined ideas have emerged:

Microbiome Perspective: Many experts now frame it in terms of biodiversity. The “biodiversity hypothesis” suggests that contact with a wide variety of harmless environmental microbes – in soil, plants and animals – is key to immune tolerance. This goes beyond just siblings or worms to include exposure to green spaces, fresh air, and rural soils.

Targeted Hygiene: Practitioners promote a “risk–benefit” approach to cleanliness. Surfaces and hands critical to stopping transmission of dangerous pathogens should be cleaned, while allowing benign microbes to spread in the household environment.

Despite criticisms, the core insight stands: modern life has dramatically changed our microbial exposures, and these changes coincide with the rise of allergies and immune disease.

The hygiene hypothesis has evolved into a more nuanced “microbial theory of health” rather than a call to throw out soap and water.

Practical Takeaways

For now, researchers suggest a balanced approach: encouraging healthy microbial contact without eschewing all hygiene. For example, letting babies crawl on grass, having a pet dog in the house, sharing family meals, and not overusing antibiotics can help diversify a child’s microbiome.

Breastfeeding (which transfers beneficial microbes and sugars) is beneficial, and vaginal birth when possible gives newborns a good microbial start.

At the same time, parents should still use soap and vaccines to prevent serious infections. Public health experts emphasize “targeted hygiene”: sanitize what must be sanitary (to avoid real pathogens), but otherwise don’t worry about everyday germs.

In short, build a rich microbiome through diet, nature and social contact, while maintaining sensible cleaning of known hazards.

In summary, the hygiene hypothesis teaches that “too clean” an environment in early life may deprive the immune system of needed lessons.

A growing body of studies – from sibling surveys to germ-free animal experiments – supports the idea that certain microbial exposures are good for our immune training.

Yet it’s equally clear that maintaining basic hygiene to block dangerous germs remains essential. The goal is not to abandon hygiene, but to redefine it: emphasize infection control where needed, and embrace the invisible helpers (microbes) that keep our immune systems well‑tuned.

[Source]