How Grapefruit Can Accidentally Overdose Your Medication

Doctors Warn That This Common Fruit Can Turn Safe Prescriptions Toxic

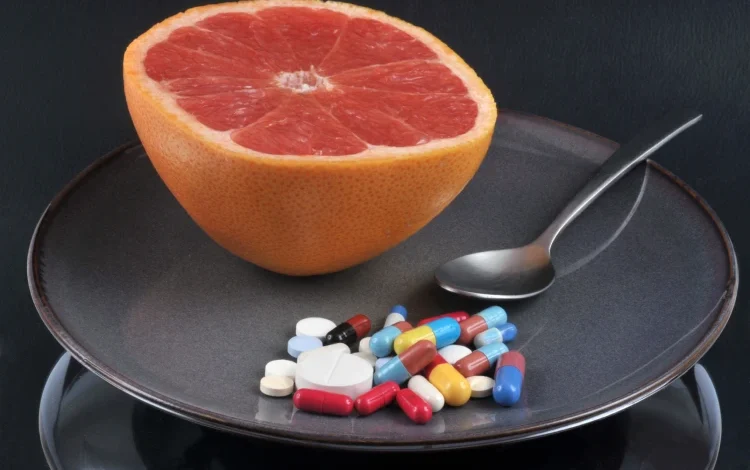

Most of us trust the fine print on prescription bottles will keep us safe. But there’s one warning that often slips past unnoticed—and it involves a fruit many people consider part of a heart-healthy diet. Grapefruit, known for its vitamin C punch and refreshing flavor, can interfere with dozens of prescription drugs in ways that are not just inconvenient, but potentially life-threatening.

So why don’t more people know about it? The answer has less to do with chemistry and more to do with how we think about food, labels, and medicine.

The Quiet Risk in the Fruit Bowl

The issue isn’t new. Researchers identified in the early 1990s that grapefruit contains natural chemicals called furanocoumarins, which interfere with how certain medications are broken down in the body.

These naturally occurring chemicals block an enzyme in the gut known as CYP3A4, which normally helps break down many oral medications.

When this enzyme is blocked, the drug can build up in the body to toxic levels—without the patient doing anything wrong other than drinking juice.

This interaction often goes unnoticed because it rarely triggers symptoms right away. Instead, it slowly amplifies the strength of the drug over time, which can lead to unexpected complications.

So Why Aren’t People Paying Attention?

Despite the science, awareness of this interaction remains low. According to Dr. David Bailey, the clinical pharmacologist who first discovered the effect, many patients never see the warning at all.

Part of the problem is labeling. Medication guides often include a vague note like “Do not take with grapefruit juice” buried in sections most patients don’t read. Some labels only mention “citrus interactions” without explaining why or which fruits. And very few healthcare providers emphasize it unless directly asked.

Even more confusing: not all drugs within a class are affected. For example, while simvastatin interacts with grapefruit, pravastatin does not. Without specific guidance, patients may assume all statins are safe, or unsafe, creating more confusion.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Adults over the age of 45 are particularly at risk when it comes to grapefruit-related drug interactions. This age group is more likely to take multiple prescription medications daily, many of which fall into the category of drugs affected by grapefruit.

They also tend to consume grapefruit or its juice more regularly as part of heart-healthy diets. Compounding the risk is the fact that drug metabolism tends to slow down with age, making older adults less capable of handling sudden spikes in medication levels.

A dangerous combination can occur when someone starts a “healthy eating plan” that includes grapefruit without consulting their doctor. And because older adults have less ability to adjust to high drug concentrations, the consequences can include low blood pressure, kidney damage, internal bleeding, and even sudden cardiac death.

A Real-World Reminder

Consider this: A 68-year-old retiree in Mumbai began eating a half grapefruit each morning after watching a wellness segment on TV. She was already on blood pressure medication, but the label said nothing about grapefruit. Within a week, she experienced dizzy spells and ended up hospitalized with dangerously low blood pressure.

Only later did her doctors trace the problem back to her “healthy” breakfast choice. It wasn’t negligence—it was a gap in communication.

Fruits like Seville oranges, along with pomelos and certain varieties of limes, also contain furanocoumarins, the same compounds responsible for grapefruit’s drug interactions.

Most people wouldn’t think twice about tossing a bit of citrus into a salad or squeezing some into a drink, but when you’re on specific medications, even these seemingly minor additions can intensify the effects and pose unexpected health risks.

And here’s what’s truly concerning: these interactions can happen even if you eat the fruit hours before or after your medication. That’s because CYP3A4 remains blocked for up to 24 hours or more after exposure.

What Needs to Change?

Addressing the risk requires more than just clearer labeling. Healthcare providers—doctors, pharmacists, and even trusted medical websites—need to make it standard practice to inform patients about grapefruit interactions, especially when prescribing drugs known to be affected.

Patients, in turn, should be proactive: they should ask whether their prescriptions interact with grapefruit or related citrus fruits, read the full medication leaflets instead of relying solely on sticker warnings, and inform their healthcare provider about any new dietary habits, even ones that seem as harmless as adding fruit to breakfast.

Most interactions with grapefruit are avoidable. Many drugs have safe alternatives. And for those that don’t, skipping grapefruit is a small sacrifice for preventing serious complications.

In an age when personalized medicine is becoming the norm, we shouldn’t be tripped up by a breakfast fruit. But until warnings are clearer—and awareness is higher—this forgotten label will keep putting people at risk.